Lockdown (2000 film)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| Lockdown | |

|---|---|

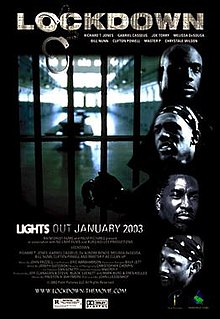

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Luessenhop |

| Produced by | Mark Burg Jeff Clanagan Oren Koules Stevie Lockett |

| Written by | Preston A. Whitmore II |

| Starring | Richard T. Jones Gabriel Casseus Master P David Fralick De'Aundre Bonds Melissa De Sousa Bill Nunn Clifton Powell Sticky Fingaz Joe Torry |

| Music by | John Frizzell |

| Cinematography | Christopher Chomyn |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures (UK) TriStar Pictures (International) Rainforest Films (US) |

Release date | September 15, 2000 (UK & International release), February 14, 2003 (US release) |

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $449,482[1] |

Lockdown is a 2000 drama film, directed by John Luessenhop and starring Richard T. Jones, Clifton Powell, David Fralick, and Master P. The film was produced by Master's P's No Limit Films,[2] a division of his No Limit Records label.

Plot[edit]

In Albuquerque, New Mexico, Avery Montgomery (Jones) is taking time off from college to spend time with his girlfriend Krista Wells (Melissa De Sousa), and help raise their young son. Avery is an avid swimmer and develops to a championship level, and as a result of a particularly impressive win which catches the eye of a scout, he gets the opportunity for a possible scholarship at a college.

Cashmere (Casseus), a drug dealer, happens to be one of Avery's best friends, despite the fact that their personalities and lifestyles are quite different, Avery being the one who stays out of trouble. With their barber friend Andre "Dre" Wells (De'aundre Bonds) who is also Krista's Brother, the trio have been friends since childhood.

Earlier in the day before the swim meet, Cashmere had a run-in with Broadway (Sticky Fingaz), another dealer who works under Cashmere in the hierarchy. Broadway happened to be short on money in his return, and it angered Cashmere, who proceeds to kick Broadway down a flight of metal stairs and pull out a gun to assert his power, threatening to kill him if he does not pay back what he owes.

Broadway runs off, but vows to get revenge and, after an attempted robbery later in the day where he shoots and kills a woman at a drive-through, he wipes off his gun and tosses it into the backseat of Cashmere's open convertible when he is out of the car, which looks similar enough to Broadway's car to be mistaken for it.

After the swim meet, Cashmere and Dre, who are there to cheer him on, convince Avery to come out and celebrate his big victory. At a certain point, Dre, who is riding in the back seat, finds the gun, and questions Cashmere about it but Cashmere has no idea where it came from. As they were arguing over how to get rid of it, some cops spot them and, thinking their car looks similar to Broadway's, pull them over. One of the officers orders them out of the car at gunpoint, which they obey, but a few moments later Cashmere's pit bull runs toward the officer, who shoots the dog dead. Cashmere pulls out the gun in anger, but is shot in the shoulder and knocked down.

After being wrongfully convicted of Broadway's crime, the three are sent to the same prison to serve a ten-year prison sentence. Each man experiences different events: Cashmere beats up and threatens his cellmate; Dre is raped and turned to a prison sex slave by his psychotic White Supremacist cellmate named Graffiti (David "Shark" Fralick), who controls much of the prison's drug flow and is the leader of a neo-Nazi gang; and Avery meets and befriends an old cellmate named Malachi Young (Clifton Powell) who has been in jail for 18 years and is nearing the end of his sentence. Cashmere begins to work for Graffiti's rival, Clean Up (Master P), another drug trafficker who Cashmere knew pior to getting locked up.

Meanwhile, Charles Pierce (Bill Nunn), the college scout who Avery met on his fateful night, believes that Avery was wrongfully convicted and decides to help him appeal the sentence, along with his daughter, a lawyer. Avery is resentful and resistant at first, towards both Pierce and Krista (at one point yelling at her to never come back because it "would do them both better") but eventually accepts their visitations and attempts to help.

Graffiti continues to successfully smuggle drugs into prison by swallowing packets of drugs brought by his girlfriends. In a fight for the control of the prison drug trade, Clean Up successfully executes a plan to kill a rival drug dealer, a former professional football player working for Graffiti, and the man is killed with a barbell crushing his windpipe, which is made to look like an accident. A corrupt guard named Perez who is on Graffiti's payroll warns the neo-Nazi not to retaliate but Graffiti and the gang kill one of Clean Up's men anyway. His dead body is found in the prison laundry room, and the warden orders a lockdown to punish the prisoners. The prisoners suffer isolation in their cells while Graffiti continues to rape Dre.

After the lockdown finally ends, Dre starts injecting heroin and one day snaps and attacks Graffiti. Graffiti eventually gets the upper hand back and starts to beat him up. Avery, who was on his way to see Dre after his girlfriend asked him to look after him, despite Malachi's warnings not get involved, jumps in to protect Dre and starts pummeling Graffiti. A brawl erupts as the other Neo Nazi's come to Graffiti's aid and Malachi jumps into the fight, throwing one of Graffiti's men over the second floor railing, before the COs subdue the inmates.

Malachi, Avery, Graffiti, Dre, and the others involved have to go to a disciplinary hearing, in which Malachi, in an act of sacrifice (after being allowed to go in first upon his request), takes responsibility for the entire incident to spare Avery a discipline record and assault charge. Malachi also intimidates the disciplinary panel by getting into an episode of rage to makes his confession believable, which ends up with him being transferred to another prison. Avery is grateful to Malachi and the old prisoner leaves Avery a parting gift - a copy of Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man with a shank hidden inside. Avery soon gets a new young cellmate who he tries to mentor just as Malachi mentored him.

Cashmere and Clean Up approach Dre telling him that he must kill Graffiti or he would soon end up being killed by him. Cashmere offers Dre drugs. Soon, high on drugs, Dre approaches Graffiti at a gospel concert at the prison and stabs him to death as revenge. Dre is himself killed with a blow to the head from the nightstick of the crooked guard Perez.

Soon afterward, Clean Up's drug mule is arrested on intel provided by Cashmere's vengeful cellmate. Furious, Clean Up believes there is an informant who sabotaged his operation. He blames it on the new arrival Cashmere, but Cashmere denies his involvement. Cashmere suggests that Avery must have been the informant as they revealed their drug smuggling operation to him when they unsuccessfully tried to recruit him. Clean Up orders Cashmere to kill Avery.

Tensions run high in the prison with the power vacuum after Graffiti's death and soon a riot spontaneously develops in the prison yard, with prisoners from rival gangs jumping in to settle their scores. In the chaos, during which a number of COs and prisoners are killed, including the young inmate that Avery was mentoring, as well as Perez, Cashmere attacks Avery with a shank and they get into a mortal combat. Cashmere is about to kill his former friend when he has a change of heart and wavers. Clean Up then shows up and attacks Cashmere and Avery but ends up being stabbed to death by Cashmere. Cashmere and Avery are about to embrace but a prison guard shoots Cashmere dead, thinking he was going to attack Avery.

Broadway, likely affected by the appeals of Avery's visiting girlfriend to exonerate Avery and help his son have a father, hangs himself in prison and writes a confession to the murder of the fast food clerk for which Avery was framed. Charles Pierce and his daughter bring the confession to a judge who grants Avery a release. Avery is shortly released. He enjoys swimming in the pool again and the company of Krista and his son.

Cast[edit]

- Richard T. Jones as Avery Montgomery

- Gabriel Casseus as Cashmere

- De'Aundre Bonds as Andre "Dre" Wells

- Melissa De Sousa as Krista Wells

- Bill Nunn as Charles Pierce

- Clifton Powell as Malachi Young

- Sticky Fingaz as Broadway

- Joe Torry as Alize

- Master P as Clean-Up

- David "Shark" Fralick as Graffiti

- Andrew Divoff as Mexican Gendarme (Graffiti friend)

- Lloyd Avery II as Nate

- Dianna St. Hilaire as Martina

Production[edit]

The film's prison scenes were shot on location at the then-closed down New Mexico State Penitentiary."[2]

Release[edit]

Lockdown was screened at the 2000 Toronto International Film Festival and released September 15, 2000 internationally. It closed out the 2001 Hollywood Black Film Festival.[3] Lockdown was released in the U.S. on February 14, 2003.

Box office[edit]

At the end of its box office run, Lockdown earned a gross of $44948 in North America. For the opening weekend of February 14–16, 2003, the film grossed $199,000 while playing in 750 theaters.[1]

Critical reaction[edit]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 58% "rotten" approval rating, based on 12 reviews, with an average score of 5.8/10. The Washington Post's Stephen Hunter wrote, "What makes the movie memorable is its authenticity."[4] Tom Long of The Detroit News wrote of the film, "Despite a low budget and predictable story line, Lockdown has undeniable power to it, fired by some fine performances and a terrifying portrayal of prison life that rings disturbingly true."[5]

Steve Murray of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, wrote, "though over-the-top and simplistic, the film has a punchy B-movie grit and gusto."[6] Dennis Harvey of Variety wrote that, although the film was "competently made and generally credible, [the picture] lacks the writing depth or directorial distinction needed to reinvigorate well-trod bigscreen big-house conventions." He felt that the film would have more appeal "in ancillary markets than at theaters."[2]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Lockdown at Box Office Mojo

- ^ a b c Harvey, Dennis."Review: 'Lockdown'." Variety (Sept. 22, 2000).

- ^ Basham, David. MASTER P, SILKK, C-MURDER CAST IN PRISON FILM," MTV.com. (Feb. 5, 2001).

- ^ Hunter, Stephen. "Queasy Does It: 'Lockdown' Serves Up Grimmest of Tales," The Washington Post (February 14, 2003).

- ^ Long, Tom. Lockdown review. The Detroit News (Feb. 14, 2000).[dead link]

- ^ Murray, Steve. Lockdown review, Archived 2006-02-12 at the Wayback Machine The Atlanta Journal-Constitution (Feb. 13, 2003).

No comments:

Post a Comment