Robert Cornelius

Robert Cornelius | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 1, 1809 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | August 10, 1893 (aged 84) Frankford, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Laurel Hill Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Photographer, lamp manufacturer |

| Spouse(s) | Harriet Comly (m. 1832; died 1884) |

| Children | 8 |

Robert Cornelius (/kɔːrˈniːliəs/; March 1, 1809[2] – August 10, 1893) was an American pioneer of photography and a lamp manufacturer.

Early life and career[edit]

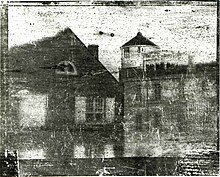

Cornelius was born in Philadelphia to Sarah Cornelius (née Soder) and Christian Cornelius. His father had immigrated from Amsterdam in 1783 and worked as a silversmith before opening a lamp-manufacturing company.[3][4] Robert Cornelius attended private school as a youth, taking a particular interest in chemistry.[5] In 1831, he began working for his father, specializing in silver plating and metal polishing. He became so well renowned for his work that shortly after the daguerrotype was invented, Cornelius was approached by Joseph Saxton to create a silver plate for his daguerreotype of Central High School in Philadelphia. It was this meeting that sparked Cornelius's interest in photography.[citation needed]

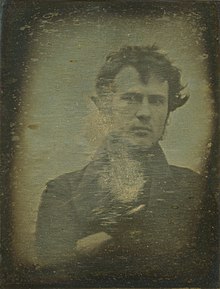

With his own knowledge of chemistry and metallurgy, as well as the help of chemist Paul Beck Goddard, Cornelius attempted to perfect the daguerreotype. Around October 1839, at age thirty, Cornelius took a self-portrait outside of the family store. The daguerreotype produced is an off-center portrait of a man with crossed arms and tousled hair. While Daguerre's photograph of the Boulevard du Temple, taken one year earlier, has since been discovered to incidentally include two human figures on the sidewalk (they just happened to stay motionless long enough to imprint on the exposure),[6][7] Cornelius' image – which required him to sit motionless for 10 to 15 minutes – is the oldest known intentional photographic portrait/self-portrait of a human made in America,[8] preceded by at least some months by portraits taken by Hippolyte Bayard in France.[9]

Cornelius would operate two of the earliest photographic studios in the U.S. between 1841 and 1843, but as the popularity of photography grew and more photographers opened studios, Cornelius either lost interest or realized that he could make more money at the family gas and lighting company.[citation needed]

Personal life[edit]

Cornelius married Harriet Comly (sometimes spelled "Comely") in 1832. They had eight children: three sons and five daughters.[10]

Later years and death[edit]

Cornelius retired from his family's business in 1877.[11] In his later years, he lived at his country home in Frankford, Philadelphia. Cornelius was also an elder at the Presbyterian Church, where he was a member for fifty years.[12] He died at his Frankford home on August 10, 1893.[11][13]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Meehan, Sean Ross (January 1, 2008). Mediating American Autobiography: Photography in Emerson, Thoreau, Douglass, and Whitman. University of Missouri Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8262-6640-8.

- ^ American Journal of Photography, Volume 14. Thos. H. McCollin & Company. 1893. p. 420.

- ^ Hannavy, John, ed. (2013). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Routledge. p. 338. ISBN 978-1-135-87327-1.

- ^ Cornelius, Ellanor Frances (1926). History of the Cornelius Family in America: Historical, Genealogical, Biographical; Containing a History of the Name from 212 B.C. and a Complete Genealogical Chart from 1639 to 1926, with Affiliated Families in Direct Line. Also Short Stories and Biographical Sketches and Illustrations. p. 37.

- ^ Barger, M. Susan & White, William B. (2000). The Daguerreotype: Nineteenth-Century Technology and Modern Science. JHU Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780801864582.

- ^ Jackson, Nicholas (October 26, 2010). "The First Photograph of a Human". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ Withnall, Adam (November 5, 2014). "This is the first ever photograph of a human – and how the scene it was taken in looks today". The Independent. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ Hannavy, John (December 16, 2013). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Routledge. p. 339. ISBN 978-1-135-87327-1.

- ^ Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.); Newhall, Beaumont, 1908- (1937), Photography 1839-1937 : with an introduction by Beaumont Newhall, The Museum, p. 39, 102CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Hannavy 2013 p.340

- ^ a b American Journal of Photography. Thos. H. McCollin & Company. 1893. p. 420.

- ^ American Journal of Photography, Volume 14 1893 pp.420–422

- ^ Society, American Philosophical (1893). Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. American Philosophical Society. p. 242.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Cornelius. |

No comments:

Post a Comment